poetry + community + translation

Through a voice at once intimate and collective, Lucas Juárez expands the powerful presence of Tutunakú roots to open up territories and to interweave desirous bodies, dream relationships, and the memories of women ancestors. This beautiful translation by Wendy Call and Whitney DeVos, in a precious handmade edition, affirms the trilingual (Tutunakú, Spanish and English) as an ethical strategy of listening to and translating the world. Red Seed collects twelve poems of women's sexualities and spirits in which body, language and territory are political spaces that Indigenous memory expands within and renews.—Maricela Guerrero, author of The Dream of Every Cell

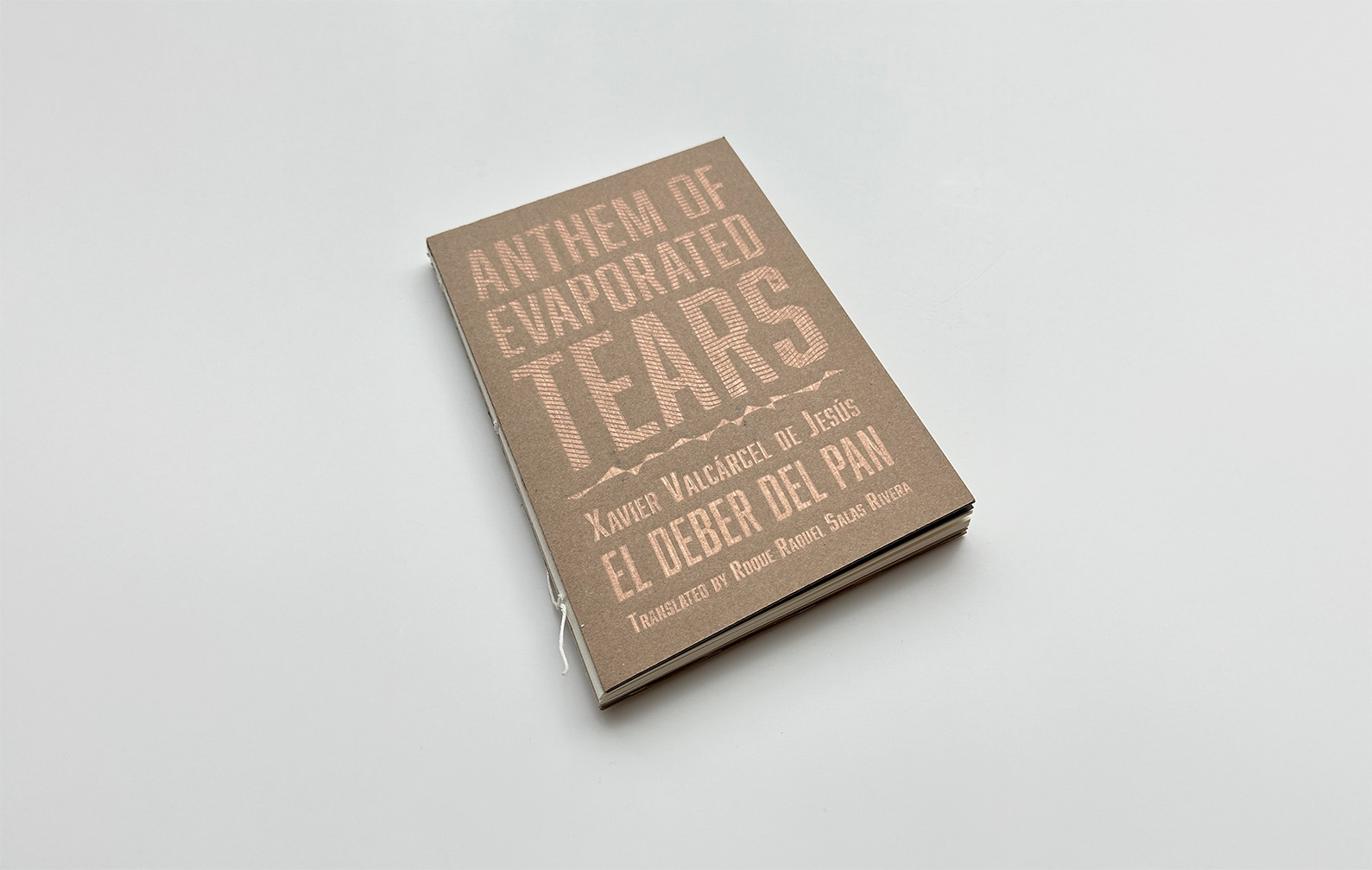

Anthem of Evaporated Tears | Xavier Valcárcel de Jesús | Tr. Roque Raquel Salas Rivera

Xavier Valcárcel’s El deber del pan struck me with full force upon publication—“changed” feels far too slight. Like many, I came to read it as a testament to a life lived and a life still living and set ablaze by our own conflagrations. In the conspiracy of translation, Roque Raquel Salas Rivera kneads Valcárcel’s violence and tenderness, its intimacy and flight, extending the book’s position as an indelible landmark in our literature. It sings with generous compassion, in English as it does in Spanish—not only with fealty, but with profound care. Here is the work of our hands, which nourishes us and must continue to feed. This book is sustenance and provocation, opening our eyes to the tender, brutal realities we carry within us, and through which we are made.—Ricardo Alberto Maldonado, author of The Life Assignment

Bodies Found in Various Places | Elvira Hernández | Tr. Daniel Borzutzky and Alec Schumacher

Elvira Hernández wrote her poem “The Chilean Flag” after she herself had been detained and tortured by the dictatorship for not complying with its lies. While Chileans were trained to look the other way, to go quiet by this terror, Elvira Hernández wrote a poem that could not be printed. Yet, the poem escaped like a prisoner and began circulating in Xeroxes, from hand to hand, until ten years later it was finally printed in Buenos Aires. In Elvira Hernández’s poetry, each line restores the right of words to speak. Each word becomes a healer, a prayer for a wounded, enslaved humanity forced to obey the rule of profit over life.—Cecilia Vicuña, author of Spit Temple

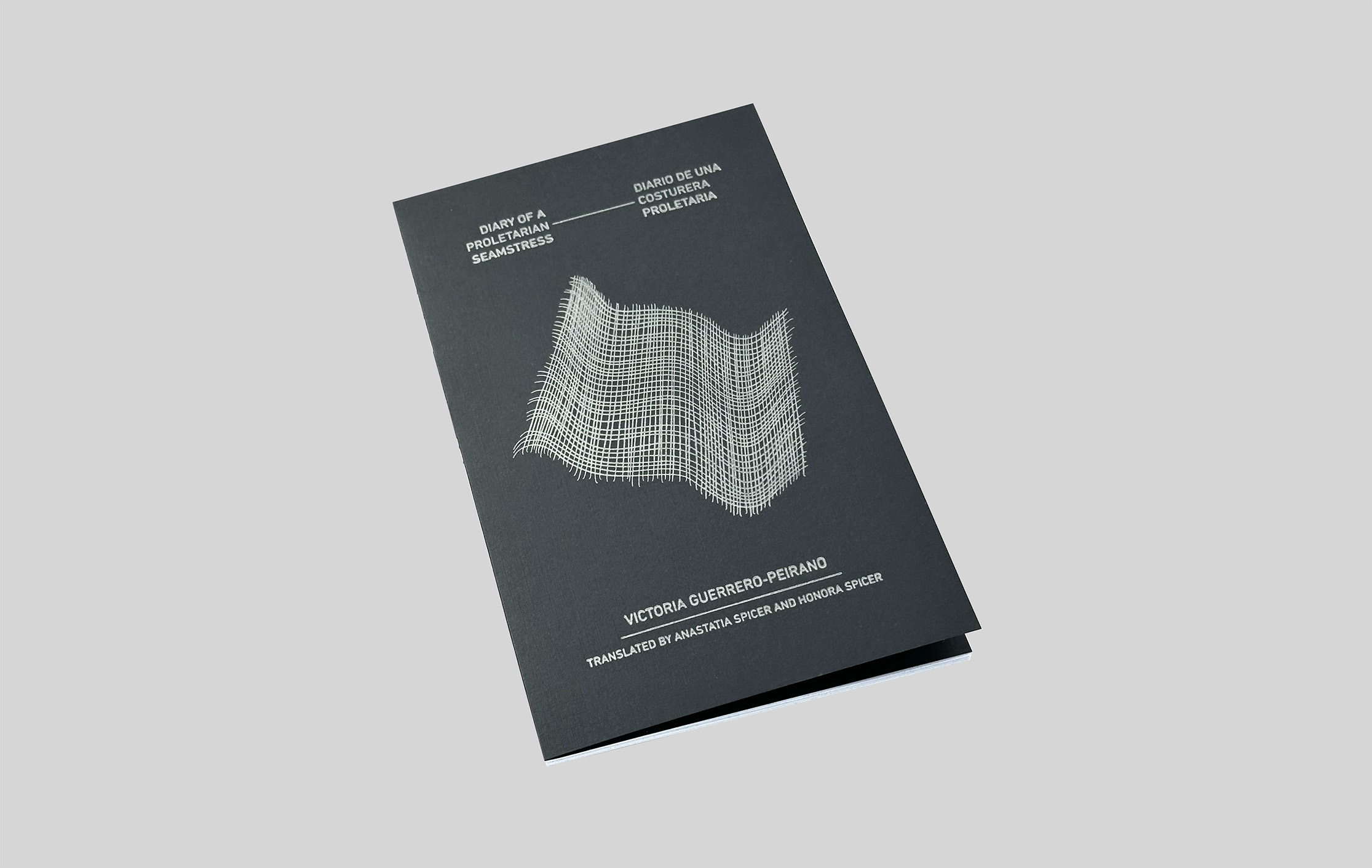

Diary of a Proletarian Seamstress | Victoria Guerrero-Peirano | Tr. Anastatia Spicer and Honora Spicer

![]()

In this beautifully woven translation, Victoria Guerrero’s Diary of a Proletarian Seamstress is a vindication of our mothers and grandmothers, who toiled in the dark, sewing and knitting, and of all the women in factories trying to satisfy our hunger for fast fashion. With each line, Guerrero rips through the seams of sexist and classist distinctions that elevate fine art above handicraft, professors above factory workers, and writers above seamstresses. From the luminous frayed threads emerge the shared silences and rage of these women, which, woven together, form a sturdy but fluid textile that invites us to consider and acknowledge the price of their invisible labor.—Rosa Alcalá, author of YOU

In this beautifully woven translation, Victoria Guerrero’s Diary of a Proletarian Seamstress is a vindication of our mothers and grandmothers, who toiled in the dark, sewing and knitting, and of all the women in factories trying to satisfy our hunger for fast fashion. With each line, Guerrero rips through the seams of sexist and classist distinctions that elevate fine art above handicraft, professors above factory workers, and writers above seamstresses. From the luminous frayed threads emerge the shared silences and rage of these women, which, woven together, form a sturdy but fluid textile that invites us to consider and acknowledge the price of their invisible labor.—Rosa Alcalá, author of YOU

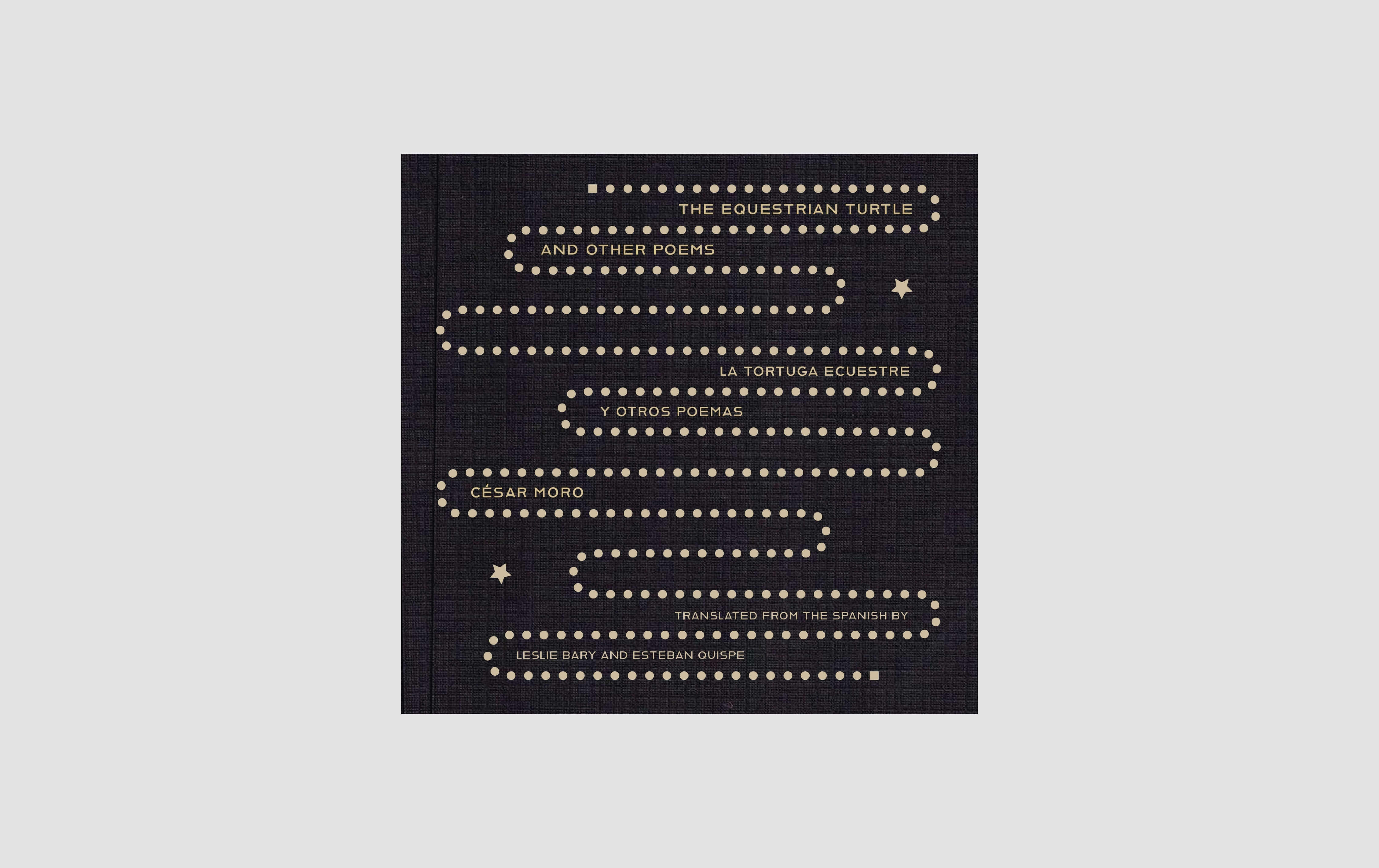

The Equestrian Turtle and Other Poems | César Moro | Tr. Leslie Bary and Esteban Quispe

César Moro’s The Equestrian Turtle joins Alice Rahon’s Shapeshifter and Joyce Mansour’s Emerald Wounds in making available in English important work written under Breton’s influence but excluded from Surrealism’s official history. In this document of romantic devotion and erotic obsession, Moro offers his own “delirious, sublime interpretation of reality,” a sensorium as open to “The total loss of speech of breath” as to “The fine, secluded odor of your armpits.” Bary’s and Quispe’s marvelous translations honor the “shattered economy” of the love affair while also admitting us into the felt presence of Moro’s beloved with his “fabulous, smoky mane.” Lit by love’s “incendiary body,” these queer poems burn with hallucinatory and rhapsodic immediacy.—Brian Teare, author of Poem Bitten by a Man

String Theory | Karen Villeda | Tr. NAFTA

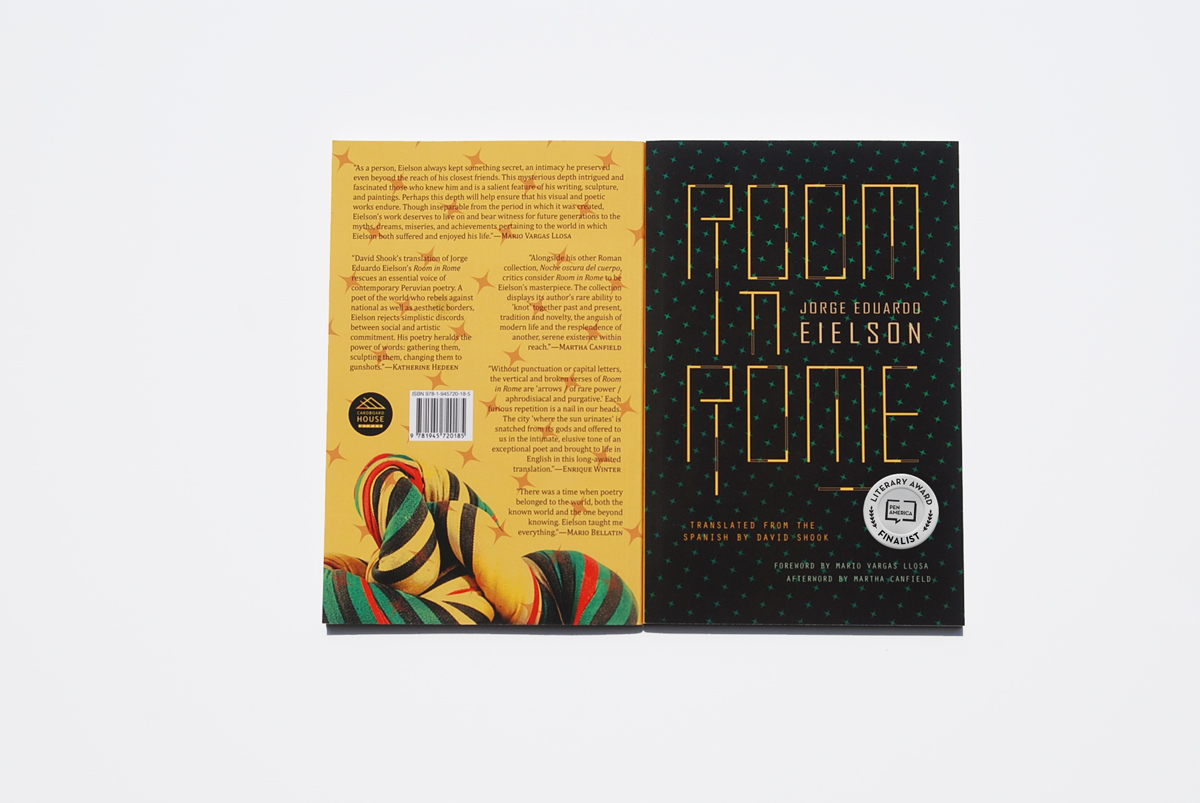

The Eielson Bundle: Special Editions for Jorge Eduardo Eielson’s Centennial

Only 100 bundles available! Celebrate with us the centennial anniversary of queer poet Jorge Eduardo Eielson, one of the 20th century’s most important artists. The Eielson Bundle includes Dark Night of the Body, an art chapbook sewn and printed by hand in Cardboard House Press workshops; a limited-edition bilingual tote bag with Eielson’s visual poem Poetry in a Bird’s Form; and a bilingual art postcard of Poetry in E Major, all brilliantly translated for the first time by Shook.

--- ---“An influential midcentury Peruvian poet who exiled himself to Europe after publishing the initial works that made him a legend in his home country (...) one of Latin America’s most important wordsmiths.”—World Literature Today

Dark Night of the Body | Jorge Eduardo Eielson | Tr. Shook

Dark Night of the Body showcases Jorge Eduardo Eielson’s poetic abilities at the peak of his powers. Hidden for years in the silence of a drawer, these poems were written in Rome in 1955 but only published in their definitive form in 1989. Querying the poet’s deepest identities, this collection reflects on the precariousness of the body by dismantling its materiality. Eielson guides us simultaneously through pleasure, pain, and play, as he redefines the limits of his biological condition, gender, and political/poetical pronouncements. Brilliantly translated by Shook, this bilingual edition of Dark Night of the Body proves essential to understanding the life and work of one of the twentieth century’s most important artists.

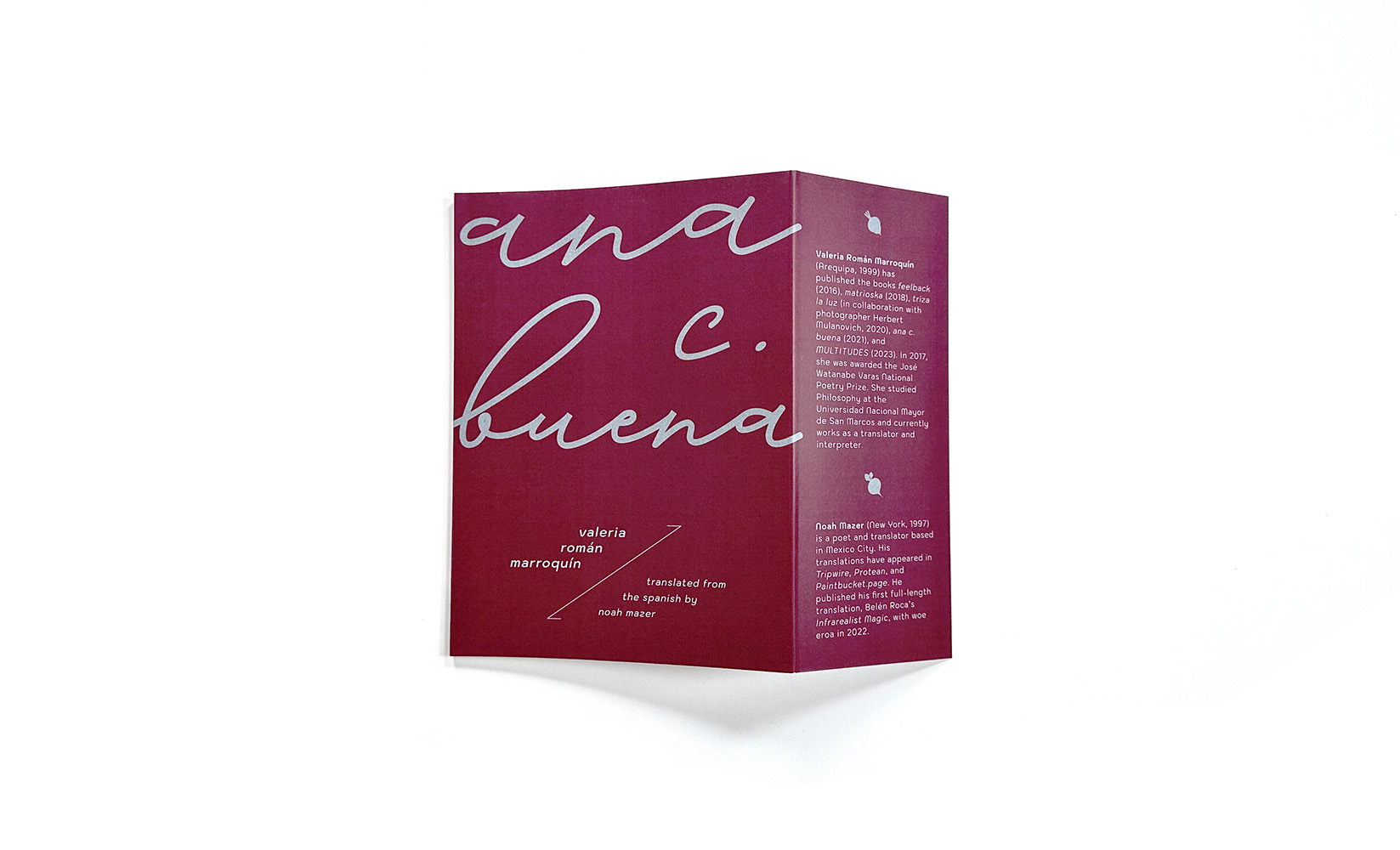

ana c. buena | Valeria Román Marroquín | Tr. Noah Mazer

In a searing manifesto-poem of late capitalist debt, hunger, and women’s labor, Valeria Román reconstructs the survival of young migrant and worker ana c. buena amid the so-called Peruvian "economic miracle" and its turbulent political space. Grappling with the meaning of care and exhaustion in an extractive economy, this collection reveals the scale of domestic routine, so easily rendered invisible by historical records, knotted into the macroeconomic scale of geopolitical forces. Hungry, ana inhabits a world that inscribes her as expendable, as experts announce “miracle bonanza times.” With a subsuming rhythm, sensory evocation, and dark humor, Román destabilizes writing itself in the face of a precarious “social totality.”

BRIDGES | Alicia Genovese | Tr. Daniel Coudriet

In one evocative scene after another, Genovese crosses both literal and metaphorical bridges to explore the transformations in a landscape, a family, an era, and a self over time, uttering “nomenclatures / that refuse / the anonymity / of a non-place / and affirm / a unique space / with a skidding / of images passed by, / returned in perception.” Coudriet’s translation of this rich work flows along as whole and complex as the body of a river: gentle, formidable, sonorous, full of surprises.—Robin Myers

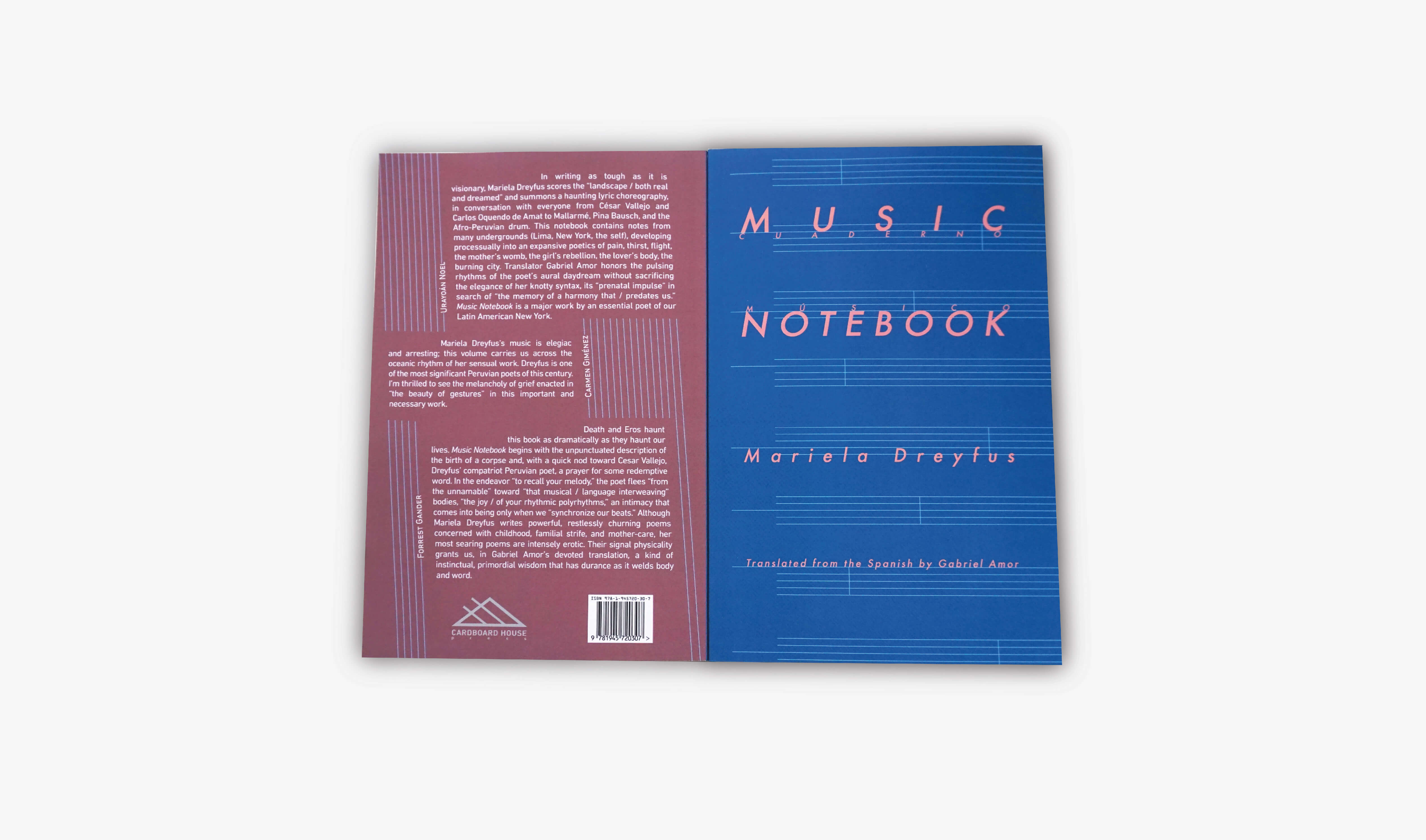

MUSIC NOTEBOOK | Mariela Dreyfus | Tr. by Gabriel Amor

In writing as tough as it is visionary, Mariela Dreyfus scores the “landscape / both real and dreamed” and summons a haunting lyric choreography, in conversation with everyone from César Vallejo and Carlos Oquendo de Amat to Mallarmé, Pina Bausch, and the Afro-Peruvian drum. This notebook contains notes from many undergrounds (Lima, New York, the self), developing processually into an expansive poetics of pain, thirst, flight, the mother’s womb, the girl’s rebellion, the lover’s body, the burning city. Translator Gabriel Amor honors the pulsing rhythms of the poet’s aural daydream without sacrificing the elegance of her knotty syntax, its “prenatal impulse” in search of “the memory of a harmony that / predates us.” Music Notebook is a major work by an essential poet of our Latin American New York.—Urayoán Noel

POETECHNICS | Yaxkin Melchy | Tr. by Ryan Greene

Yaxkin Melchy's Poetechnics is an invitational poetic provocation that both transforms and transcends the traditional categorization(s) of poetry and science. Drawn from the first two full-length books in his decade-in-the-making project, THE NEW WORLD, the sci-tech poems in Poetechnics celebrate Melchy's lyrically rich and formally inventive approach to disciplinary blurring. This wonderstruck collection, dancing from the depths of the ocean to the furthest reaches of outer space, traverses circuit diagrams, binary sequences, textbook figures, and more. Here, in these thrumming bilingual pages (and their accompanying digital "transfluxions"), we witness Melchy in action, kinetic and expansive, as he invites us to dream alongside him toward "a scientific imaginary rooted in the heart.”

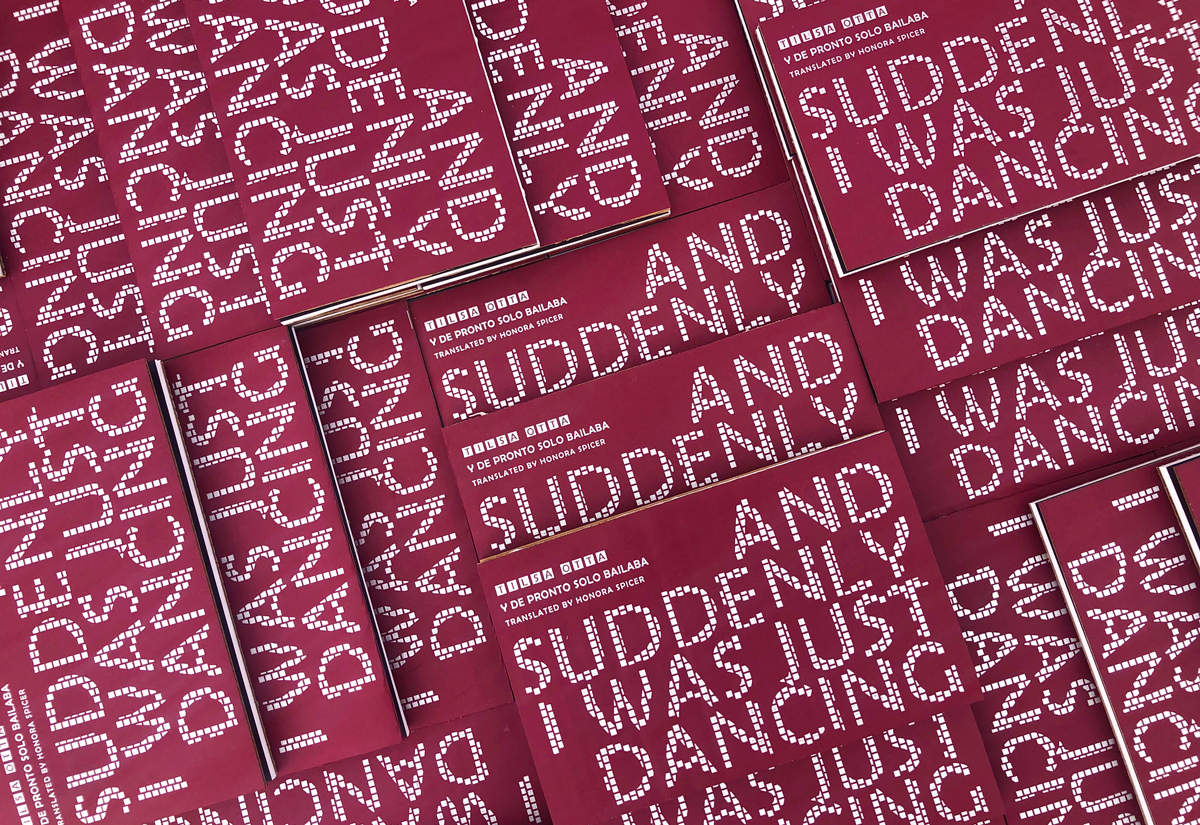

--- ---AND SUDDENLY I WAS JUST DANCING | Y DE PRONTO SOLO BAILABA | Tilsa Otta | Tr. by Honora Spicer

Tilsa Otta is one of my favorite poets, and Honora Spicer’s translations capture what is luminous about Otta’s work. This collection is nocturnal punk graffiti. She manages to make a voice that’s a little IDGAF, a little mystical into a hypnotic pulse radiating out like a bat signal in the shape of her girlfriend’s puppy. And Suddenly I Was Just Dancing is the balm for your mercury in retrograde. Bring your satellite.―Carmen Giménez Smith

x+x+x+, which is to say, the “x” that in Spanish marks out the gender binary can wheel, in Honora Spicer’s translations as much as in Tilsa Otta’s poems, into the “+” of possibility, the unapologetic celebration of appetite, savoring the spit we share in articulating the more that is already here. These are poems that call us into the “wild lyceum” where our gorgeous animality tunes its collective attention to the elegance of its own music. Otta and Spicer lead us in a “dance / supposedly obscene / that assures / Humanity’s continuance,” which is to say x+x+x+―Farid Matuk

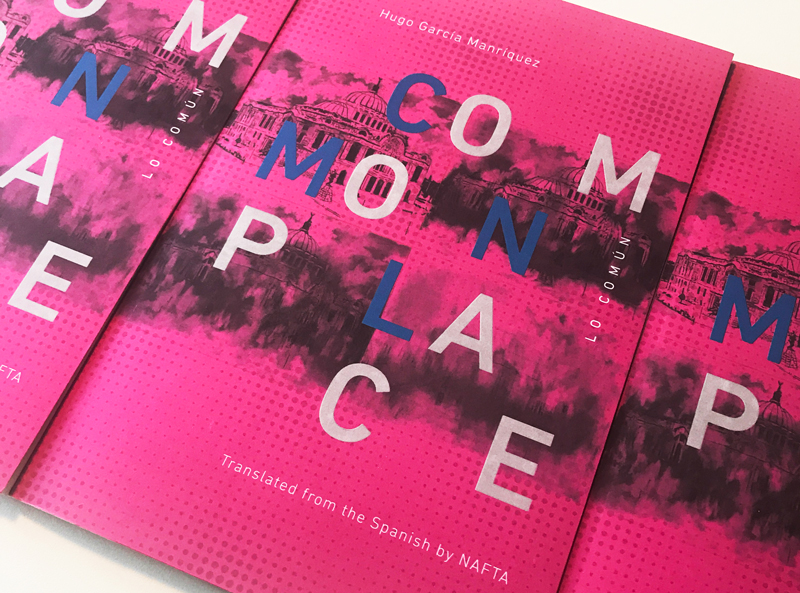

COMMONPLACE | LO COMÚN | Hugo García Manríquez | Tr. by NAFTA

Commonplace is a literary topos of the natural world, a compilation of the environmental crisis made with an eye so wide that it includes the Popul Vuh, the Palacio de Bellas Artes, and the budget of SEDENA. This makes it a nature poem that is in no way nostalgic, a political poem that is in no way nationalist, and one of the most moving poems I’ve read in a long time.―Juliana Spahr

These poems both catalog and interrupt contact between the military and the ecological in everyday contexts: how traces left by the glands of a white-tailed deer and petals from bright yellow creosote also touch Colts and Glocks and ion scanners. In doing so, they ask me to confront whether there remains anything private in my so-called private life. As García Manríquez writes, “When we read literature / we read the budget of the Mexican army.” And in that budget, we may spy the poetics of our own elegies. This compact, but frightening, book invites us to consider “The collapse of abstraction / as another form of freedom.”―Divya Victor

FUDEKARA | Liliana Ponce | Tr. by Michael Martin Shea

The work's evanescence, its ‘not being,' the composition of the void, of the space between the lines, is the art, the mastery of Liliana Ponce in Fudekara, to make present what is felt, the other reality within ‘reality,’ released by and through the brush. Her admirable reticence is a bolt of world-opening lightning.—Cecilia Vicuña

In Liliana Ponce's dekatesseral Fudekara, nimbly translated by Michael Martin Shea, all thought emits a cosmic gesture and the writing hand traces an inviting, inkwet path to the negative sublime.—Joyelle McSweeney

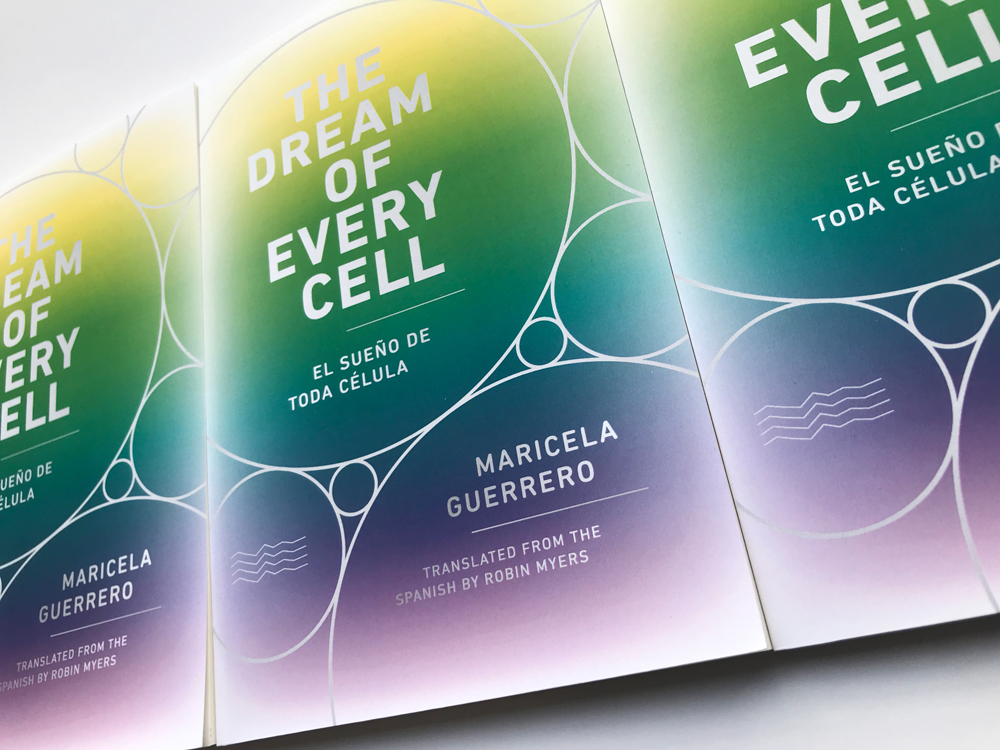

THE DREAM OF EVERY CELL | EL SUEÑO DE TODA CÉLULA | Maricela Guerrero | Tr. by Robin Myers

Maricela Guerrero leads us right back into the classrooms where many of us first encountered the scientific language that opened us to (and distanced us from) the plant kingdom. And she leads us out again, forcing us to confront the territories of devastation before she introduces us, suddenly small, into the cells, the sap in the trees, the shapes of the leaves. Everything pulses and everything shines there: language, connections among the elements, protest. What wise, warm writing by Maricela Guerrero, and what a marvelous English translation by Robin Myers, a poet herself. An essential voice in the eco-poetry being written within the Spanish language today.—Cristina Rivera Garza

Guerrero metabolizes the language of science with the languages of the environment to teach us lessons in attentiveness, care, and healing. Moreover, she protests ongoing extraction and calls us to protect the “lungs of the earth.” Reading this book felt like dreaming with cells, wolves, trees, and rivers in a place where “respiramos juntos” (“we breathe together”). This bilingual collection is a profound expression of Mexican eco-poetry.—Craig Santos Perez

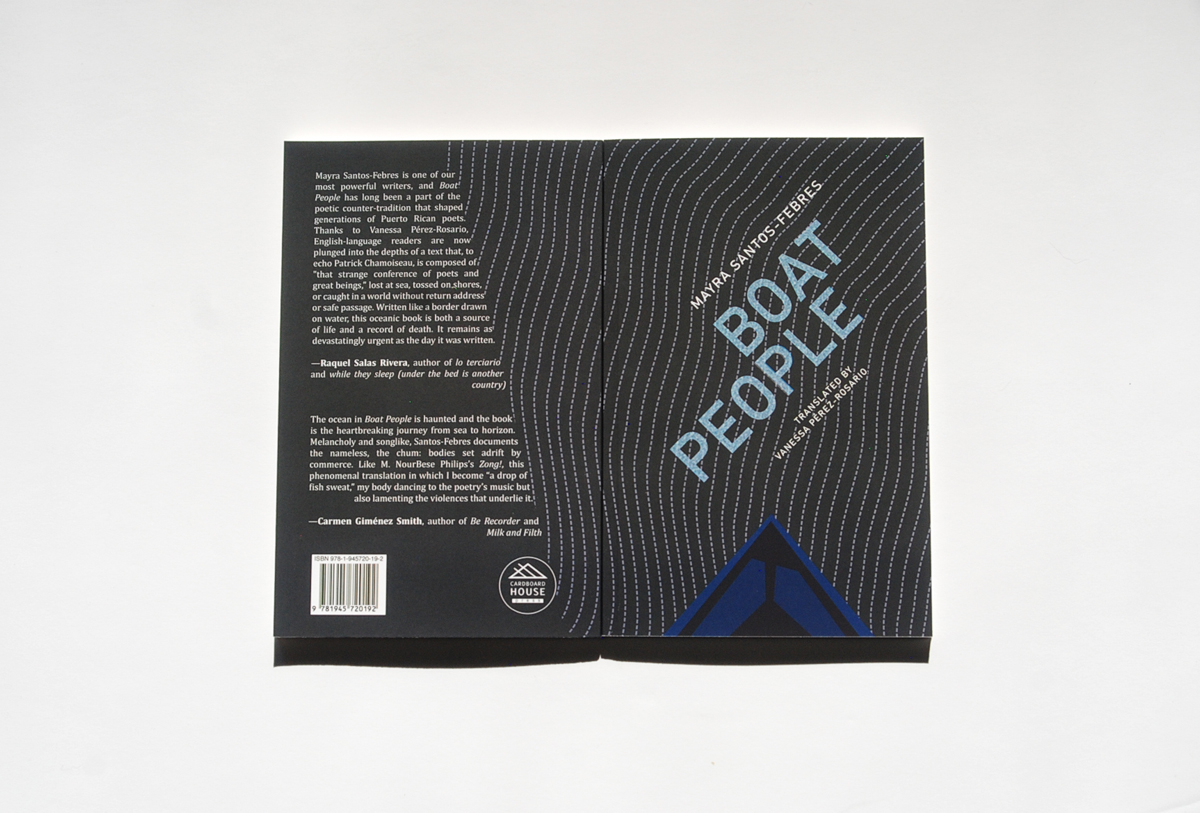

BOAT PEOPLE | Mayra Santos-Febres | Tr. by Vanessa Pérez-Rosario

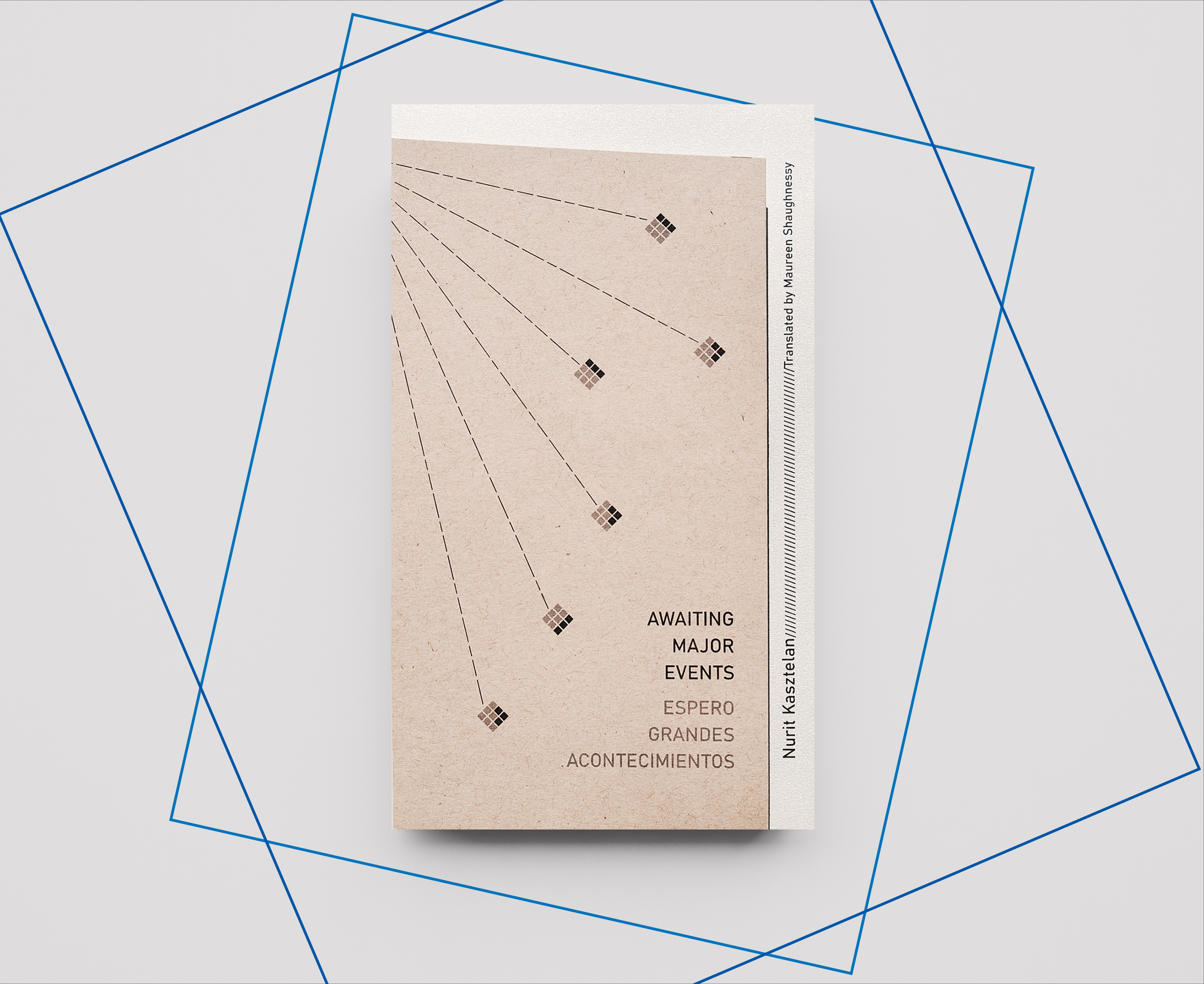

Awaiting Major Events invites us on a trip in space and time—to other rivers, other lands, where childhood and present are “tied like a knot.” Kasztelan writes with the five senses, delicately, the way you disentangle one plant from another, and so climb into fluctuation between the domestic and multiple “theres,” between the I and the “layers of other things,” between her own writing and references to the writing of others (Elizabeth Bishop, Ricardo Molinari, Irene Gruss). We arrive at the end of the book like we arrive home from a journey, “saturated with stimuli.” “What lingers after a trip?” The real possibility of getting back, or getting back to the glimmer of certain images: the filigree of a cameo, the broken branch of an olive tree, the language—with the skillful translation of Maureen Shaughnessy—of a forest that brings together the infinite and the consciousness of limit.—Silvina López Medin