︎Home

︎Catalog

︎Cartonera

︎Submissions

︎Donate

︎About

︎Contact

︎ ︎

︎ PDF Catalog

Cardboard House Press is a 501c3 nonprofit organization founded in 2014, dedicated to the creation of Spanish-English bilingual spaces through small-press publishing, community workshops, and bilingual events. We publish Latin American and Spanish poetry in translation, with a focus on innovative contemporary poetry, historical avant-garde, and social poetics. Our work acts as a platform for the exchange of ideas, uplifting new meanings that provoke connection and social action.

︎︎︎

︎Reviews

Anthem of Evaporated Tears ︎︎︎

“Consider it the perfect literary companion for your next heartbreak, or for those days when the thought of lighting his favorite sneakers on fire feels like a completely legitimate form of poetic justice…Valcárcel excavates the home with the care of an archivist and the fury of an arsonist. He understands that the domestic is the first site of the colonial, the patriarchal, the place where the “burden of bread” (el deber del pan) (40-41) is kneaded into our muscle memory…This is a deeply Puerto Rican and Dominican queer text, a chronicle from “this side of customs” (19). It maps the internal borders of identity, the hunger that is both physical and existential.”—Maria Burgos, CUNY Center for Puerto Rican Studies

“Anthem of Evaporated Tears packs into one poem the elements of nature—fire, water, earth, and air—and, into one suitcase, the ingredients of el deber del pan—egg, salt, flour, and waves—as it narrates an intergenerational break-up story—with all the frustrations and violence that domesticity and dependence cause in a spirit that wishes to fly free…The translation by Roque Raquel Salas Rivera, author of the epic poem Algarabía, is masterful.”—Giannina Braschi, Latino Book Review

Bodies Found in Various Places ︎︎︎

“The poem unfurls the flag as both national symbol and shroud, exposing how the apparatus of state violence wraps itself around the body politic. Hernandez’s writing is incandescent with resistance, transforming metaphor into protest, lament and survival.”—Leo Boix, The Morning Star

“The poems in this career-spanning anthology are, most of all, politically engaged and often visceral. They’re also formally inventive and span the sacred and the profane, sometimes in the same work.”—Tobias Carrol, Words Without Borders

“Hernández’s omnipresent personal narrative (which is not literally on the page, but can be felt) is best experienced in the opening poem/book The Chilean Flag. This book-length poem was circulated illegally, in opposition to the dictatorship, as photocopies passed hand to hand starting in 1981 until its official publication in 1991.”—Brent Ameneyro, Letras Latinas

“The six works gathered in this anthology trace a compelling arc through four decades of poetry that show Elvira Hernández’s singular commitment to chronicling oppression from the marginalized perspective that defines her “ethics of invisibility.” Readers who enter this volume are introduced to the full range of a poet whose work, written between 1981 and 2018, is finally receiving recognition in her home country. This Cardboard House Press edition serves as an accessible introduction and, at the same time, a definitive bilingual reference.”—Vicent Moreno, ReVista, The Harvard Review of Latin America

“The brilliance of Hernández’s poetic witness is in part her ability to find the downturned facet of a story and document it…The dichotomy of the reportage—at once a brilliant inspiring image of identity and an incessant detachment—is nothing short of shocking as it lays bare the contradictions inherent in a society under dictatorship rule.”—Jacqueline Balderrama, Full Stop

“Praised by Cecilia Vicuña as a poetry that “restores the right of words to speak,” Bodies Found in Various Places is a truly captivating anthology of Chilean neo-avant-gardist Elvira Hernández’s collected works.”—Paul Cunningham, Heavy Feather Review

Diary of a Proletarian Seamstress ︎︎︎

A wonderful collection by the Peruvian poet, researcher, and essayist Victoria Guerrero-Peirano, with echoes of Anne Boyer’s 2015 work Garments Against Women…it is an incredible, thoughtful work that interweaves (ah!) meditations on work, women’s historical ties to fabric-making and weaving, concepts of translation, and more into a cohesive, fascinating whole.—Rhian Sassen, Phrase Books

The Equestrian Turtle and Other Poems ︎︎︎

The body that emerges from the sea, astride a turtle, transforms day into night and night into light. That same body becomes desire, becomes pain, becomes discrete parts reserved for nostalgia’s longing—for the very memory of pleasure. This is the radiant premise of César Moro’s lyric universe in The Equestrian Turtle and Other Poems, now energized in a new bilingual edition by the inclusion of eight previously unpublished poems and seven pieces of prose poetry. These additions bring us tragically closer to the voice of a timeless, irreverent, queer author—and shape a figure more tangible, more intimately connected to the longing for a beloved body, to the feverish mirage of love ignited by the forbidden.—Nilton Maa, Full Stop

“What is most striking about this book is the proximity of language to love. “I can give you any name: sky, life, alphabet, air that I breathe”, writes Moro. Naming is the fundamental function of language, and love, in Moro’s poetry, is the infinite use of language. Uttering a word–giving a name–is an act of love. What better way to celebrate this idea than in translation?”—Madeline Kwasick, Action Books

“Leslie Bary & Esteban Quispe’s dazzling translation of Peruvian surrealist poet César Moro’s The Equestrian Turtle is a geologically illustrious work of molten greens, pearlescent dreams, and hecatomb-love. With its anaphoric verve and diamond-sharp imagery, The Equestrian Turtle is not only a meditation on the convulsive beauty of the nonhuman world, but it’s also been described as a “book of psalms” dedicated to Moro’s eight-year romance with Mexican army officer Antonio Acosta…These are shadow-dwelling surrealist love poems radiating a “diamond insanity” unlike anything I’ve read before.”—Paul Cunningham, Heavy Feather Review

String Theory ︎︎︎

String Theory by Karen Villeda, tr. by NAFTA, reviewed by Fabiana Lacau in The Whitney Review:

“The voice fractures and overlaps, into meditation on death, on suicide, on what it means to be woman, a dead woman, in a world of male violence. Lines chase each other across pages, weaving a knot which lies squarely in the chest of the book: Algo o alguien? Someone or something? Existence only through someone else’s memory. Existence by way of nonexistence.”

String Theory by Karen Villeda, tr. by NAFTA, reviewed by Kelsi Vanada in Full Stop:

So it seems especially poignant and beautiful that here, not a lone translator but rather a team of translators came together around this book in community, to give it a new expression—to respect its ambiguity and hold it up to the “Light and, and, / and light.”

(...) the most moving sections are those written in numbered lists—many of which begin in fact, as if trying to write down what is known (“she was found with a tangle of curls between her fingers”), and dissolve into speculation about what the aunt was going through at the time of her death. The translators move nimbly with the poet between forms.

NAFTA’s translators also demonstrate that their ears are wonderfully attuned to the musicality of the work, even finding resonances that fit the world of the poem but aren’t directly in the original (...) It’s a good reminder that not all is lost in translation, but rather something is often gained.

String Theory by Karen Villeda, tr. by NAFTA, reviewed by Vicent Moreno in Angel City Review:

When Teoría de cuerdas (String Theory) by Karen Villeda was first published in Spanish, it solidified her reputation as one of the most intriguing poetic voices in contemporary Mexican literature.

What emerges is not a forensic reconstruction but a poetic haunting, where the absence speaks louder than any fact, and where language—like grief—returns in broken, circling fragments (...) The fragmented structure also reflects the disjointed nature of memory, how trauma is never linear but emerges in flashes, in echoes, in what is left unsaid. In this respect, one must praise the translation by NAFTA, which captures these intricacies with precision, maintaining the tension between lyricism and conceptual complexity.

By intertwining personal loss with speculative possibilities, this is a book that stretches across dimensions, connecting past, present, and alternate realities. Villeda’s ability to weave these threads together makes the book an intimate yet expansive work, one that lingers long after reading and reverberates across emotional and intellectual registers.

String Theory by Karen Villeda, tr. by NAFTA, reviewed by Greg Bem in North of Oxford:

The poems are massive, the statements flurry and flushed, each flip of the page another step in a journey of existential intensity. Villeda’s work feels like the breath itself, a third person exploration of an autobiographical sequence.

As the book unfolds, the reader becomes privy to the aunt’s circumstances: a large, beating heart of a question. That the aunt was found dead, by hanging, is truth. That there is unknown to cause is also truth. There is doubt. There is hope. There is anger. There is impossibility: was the hanging a death by suicide, or was it the result of gender-based violence?

String Theory is a book of mourning, it is a book of cherishing, and it is a book of the resulting fury of need, of needing to know, of pushing forward, into what else but what we are yet to have. It is of connections and relations and relationships with ourselves and with others and the living the dead and being alive and being dead. This book props up our shared gaze and angles it across vast distances of knowing. The results may or may not be clear, but the process is filled with power and beauty. It is the poet’s act to remember and renew, alongside us.

ana c. buena ︎︎︎

An Allegory of the World’s Starving: ana c. buena by Valeria Román Marroquín.

Alan Mendoza Sosa on ana c. buena in Asymptote:

“The poetic speaker shifts between the extended apostrophe (addressing Ana in the second person), the first-person observer, and Ana’s own voice. This heterogenous focalization strengthens the book’s core critique of capitalist individualism, joining a growing library of Latin American poetry criticizing capitalist society, often through a feminist lens.”

“Not only does Román Marroquín critique how capitalism encourages spurious individualist desires, including the “fantasy of the individual empire / and the model life,” she also stresses how today’s global structure and its false promises remain grounded in patriarchy, and sustained by artificial gender inequality with deep historical roots.”

“This exhilarating collection and the leftist poetry traditions from which it emerges and to which it contributes could not be more refreshing.”

Reseña de ana c. buena, escrita por Gabriel Antúnez De Mayolo Kou y publicada en Latin American Literature Today:

En vez de limitarse a presentar al escrito como un ejemplo más de crítica, la presente edición muestra a ana c. buena con toda la disrupción que su publicación y circulación provoca. Al entrar desde esta radicalidad, abre la oportunidad de conectar a “ana”, la voz poética que lidera los poemas, con las múltiples voces artísticas de resistencia que han germinado en el sur global en años recientes.

Bridges / Puentes ︎︎︎

Bridges by Alicia Genovese reviewed by Greg Bem in North of Oxford:

“Alicia Genovese’s new poetry collection, Bridges, translated from the Spanish for the first time, is a fantastic, awe-inducing ramble that utilizes the bridge as a metaphor and a reference point for acute reflection and description. The Buenos Aires-based poet writes through her bridges, the bridges of Argentina, as she explores the personal, the symbolic, and the historical.”

“Genovese’s work is a contemporary commentary on crucial infrastructure that is threatened or taken for granted. As translator Daniel Coudriet briefly mentions in his afterword, the collection contains many references to 20th Century Argentinian political history, offering the reader with other, more ethereal bridges. How our infrastructure can serve as memorial, as haunt, as connector to the wailing torments of brutality, of disappeared people, of crisis.”

Music Notebook ︎︎︎

Music Notebook by Mariela Dreyfus reviewed by Diego Báez in Letras Latinas:

“It’s elliptical, rather than explicit; it points to the rich potential of memory and history, but withholds any detail to make tangible whatever lurks beneath the surface, deep within the well of the past. It’s a startlingly direct way to paint the trauma of institutionalization: white as the sanitarium’s walls, white as nightgowns, a whiteness that washes out everything around it.”

“Surely, the publication of Music Notebook marks the trailhead of new paths into 20th and 21st century Peruvian poetry for U.S. readers. With luck, sooner than later we’ll see more of Dreyfus’s existing poetry titles translated into English for US-based readers.”

Music Notebook by Mariela Dreyfus reviewed by Victoria Mallorga Hernandez in Latin American Literature Today:

"The postures in this poetry book are ever leaning, ever dissatisfied, ever sensual."

"Much of Music Notebook is a cloudy haze that becomes piercing, landing its thorny syntax into the reader’s hands."

"From the stone of madness and inherited malaise, meaning collapses only to birth more ink, a voice that sings and continues."

And Suddenly I Was Just Dancing ︎︎︎

And Suddenly I Was Just Dancing by Tilsa Otta reviewed by Natalia Chávez Gomes da Silva in Latin American Literature Today:

“I would recommend Otta’s poems to those who accept there is stability in instability, to those who find peace in contradiction: to those who often find themselves floating in the figurative vacuum of the duty-beings and the power-beings that the rules of this world switch up with frantic speed. To those who choose to launch themselves into imagined orbits, clinging to nothing but movement, acceleration, or a fleeting sensation in some pore of the skin or in some depth beneath the sternum. This book is for those who understand the beauty of disorder.”

“The translation by Honora Spicer, as she explains herself in the translator’s note, comprehends the bodily flow of Otta’s poetry, a flow that does not mean softness or silkiness, as the word might suggest. Spicer understands that, in order to transport the Peruvian author’s movement to a new code—to English—she has to couple up, like you would in a dance, and that doesn’t mean mirroring her moves, but rather following her double rhythm: that of Otta’s poetic subject and that of the world in which this subject moves.”

An Invitation by Captivation: A review of Tilsa Otta’s And Suddenly I Was Just Dancing

by Greg Bem in Hopscotch Translation:

“While described as a chapbook, the publication feels holistic and representative of such great energy and experience that “chapbook” hardly covers the work itself. This is a bold new collection of resistance and liberation, barreling down new pathways of sexuality, gender, and love.”

“In this selection, Otta’s speakers are alive and aware and actively moving across the page, dancing, or sitting still marveling at the universe.”

“When the dance floor reverberates elsewhere, Otta’s awe and intimacies are quiet and touching, mellow passions descriptive of the texture of sensuality and the beauty of the commitment to shared space.”

“The poet provides broad strokes that are fleeting and resonant, blurred images that cascade across time and space, lingering like warmth, or like echoes that urge sense through awareness of resonance. Otta’s instructional, if not choral, approach to poetry takes moments of the private, the intimate, and bridges them with intention and care.”

And Suddenly I Was Just Dancing reviewed by Cristina Correa in Action Books:

Tilsa Otta has offered us a vibrant black hole to enter and find ourselves enraptured with And Suddenly I Was Just Dancing. This poetry collection flows to its own beat of queer wonder, interconnectedness, and expansion. Opening with a visual poem that is both map and symbol for the past, present, and future, the poet seems to mark the spot (X) that inspired, inspires, and will inspire in perpetuity an abundance of possibilities (+). As in the poem “Hormone of Darkness” wherein Otta proclaims “I have three X chromosomes but I want + / +++,” alluding to a constructive desire that is vast as it is shameless. Indeed these poems, rendered into English by Honora Spicer, make a reader want more. They invite spacious surrender to the pleasures of connecting with oneself and with others in as much as they lay groundwork for finding a “playground” in a “crazy-sad world.”

And Suddenly I Was Just Dancing reviewed by Diego Baez in Letras Latinas:

“[...] themes of collectivity, reciprocity, and solidarity are central to this sampling of Peruvian poet Tilsa Otta’s ecstatic, celebratory, communitarian poetics (...) There is real pleasure, not only in the lyrical content, but also in bouncing between scripts, in reading between languages to embrace the reverberation. As Honora Spicer says in the Translator's Note, Otta’s lyrics enact a “carnal movement in Spanish,” and translating into English meant “not mimicking but moving sensuously in response.”

Poetechnics ︎︎︎

Poetechnics by Yaxkin Melchy reviewed by Kathy Wu in Rain Taxi:

“The text of Poetechnics introduces multi-valent, multi-versal registers of syntax, casting light on the logos of the world. Here the grapheme also becomes alive; while climbing an algebraicfunction, readers are both a straightforward line in two dimensionsand simultaneously “feel the wind and won’t ever think about sadness again.” The technology of language is rendered concrete, is chal-lenged to hold near-infinite registers—it mutates between notation and feeling, between algorithm and affect. What new axioms? What possible originating points? In histories and presents and futures of science, Poetechnics offers restless, green imaginations and electric possibility.”

Poetechnics by Yaxkin Melchy reviewed by London Pinkney in The Ana:

"[Poetechnics] functions as a machine [...] Throughout the collection form, language, and muse are not bent, but rather, adapted to reflect our Digital Age. Titles are shifted around the page, the poems have become diagrams. We are in an era where we consume more information than generations past. Poetechnics embodies that everythingness."

Translator Ryan Greene interviewed by Olivia Lott in Action Books:

“Yaxkin’s poems constantly catch me by surprise. The way his images jump and loop back, how the page is activated, the lyric cascades, the scales shifting, his metapoetic meditations. There’s an expansiveness here that I’ve felt grateful to spend time around. I’m also really moved by the ways he combines playfulness and critique, experimentation and heartedness.”

Commonplace ︎︎︎

Commonplace

by Hugo García Manríquez reviewed by

Judah Rubin in The Poetry Project:

“Hugo García Manríquez’s Commonplace approaches the Mexican state as an incomplete allegorical sign. Mexico, as an entity, is inseparable from the sign-system of the militarized world of the war on drugs and the ecocide of late capitalist extractivism.”

“Commonplace is firmly located in this fractured and fracturing totality (“Beside history / our own indexicality”), but, and this is where I find Commonplace to be so brilliant, the text pivots to think with the *Popol Vuh* in its consideration of the more than human world.”

Commonplace by Hugo Garcia Manriquez reviewed by Brent Ameneyro in Los Angeles Review:

“Many poets have said all poetry is political. Hugo García Manríquez takes this idea literally, and to a level unlike any other poetry book I’ve encountered. Manríquez’s Commonplace is an anti-art, anti-subjective, book-length poem that has more weapon specifications and military statistics than poetic utterances.”

“Imagining this book read cover to cover at a poetry reading, I would hear it as part art performance and part political speech. As much as it stands as a work of art, it would equally—if not more so—carry itself as a speech at a political rally.”

Commonplace by Hugo García Manríquez reviewed by Greg Bem in SPREAD:

“Poetry is proxy, a subtext for a radical envisioning of systems of domination from the state. As we read the poet’s lines, we’re told that we are reading the budget of Mexico’s Secretary of Public Security, Secretary of National Defense, Tax Administration Service, and Attorney General. The war machine that is part of the totality is inseparable from poetry; the poet calls forth the absurdity of this inseparation.”

Commonplace by Hugo García Manríquez reviewed by Cindy Juyoung Ok in Poetry Foundation:

“Hugo García Manríquez’s Commonplace, originally published in Spanish as Lo Común, erases and rearranges an increasingly militarized and nationalized Mexico City. Eight long poems gather fractal impressions of a city, listing military budget statistics, imperiled animal species, and various types of guns imported into Mexico from corporations in the United States and Western Europe.”

“Through repetitions and disintegrations, these recursive poems attempt an original form in which inventory serves as anti-narrative, a willing witness to the collapse of the city’s very architecture.”

Whitney DeVos interviews Hugo García Manríquez in Poetry Magazine: “An Exercise in Autonomy: Hugo García Manríquez on Translation.”

Commonplace by Hugo Garcia Manriquez reviewed by Michael Collins in North of Oxford:

“Hugo Garcia Manríquez begins Commonplace with a unique hybrid of invocation and manifesto, clearly announcing its meta-poetic intentions in the use of both generally conceptual language and semiotic terminology.”

“Manríquez articulates a poetics given life by what have been assumed to be “objects” and “matter” by the perspective of the dominant culture. Poems being cultural products, this revisioning necessitates the degree of self-definition we noted at the opening of the book, in order to differentiate from the inherited cultural expectations of poetry itself.”

Fudekara ︎︎︎

Fudekara by Liliana Ponce reviewed by Roz Naimi in Zyzzyva:

“Ponce finds what is pregnant in recursive, iterative action. She reminds us of how what may seem like mindless repetition might become a pathway to mindfulness. To embody an action over and over allows for endless opportunities to actualize what is at the core of one’s desire.”

Fudekara by Liliana Ponce reviewed by Tyrone Williams in Restless Messengers: Poetry in Review:

“As Shea implies in the Translator’s Note, this diaristic chapbook of fourteen poems reflect Ponce’s attempts to write herself out of her native language, out of her culture, and, idealistically, out of herself: “I chase an impossible room, to grant the spoken to another ear, another rule.” Ultimately, these meditative prose poems aspire to the condition of the unthought, a script entirely free of alphabetic and hieroglyphic languages (“I was liberating reason to the feeling of the improper, to the unspoken word.”). Even so, Ponce concedes that “Never will I free myself from these moorings.” As one might imagine, it is, finally, the struggle itself, a dance free of gravity and gravitas, that animates these quiet ruminations on the impossible.”

Fudekara by Liliana Ponce reviewed by Paul Cunningham in Action Books

“What makes Fudekara’s poems’ repetition so surreal and affecting isn’t Shea’s sharp attention to replicating the rhythm of the poet’s source language alone, but also Ponce’s resistance to time itself. It might even be fair to call Ponce’s poetry a threat to time. A threat to standards, understanding, accessibility, and order.”

Gardens ︎︎︎

Gardens by Carlos Cociña reviewed by Dennis James Sweeney in Electric Literature:

“This bilingual edition of Carlos Cociña’s poetic sequence is published in a gorgeous, hand-assembled chapbook by Cardboard House Press, a small press committed to publishing Spanish-English bilingual editions. Thoughtfully translated by Ian Lockaby, Gardens/Jardines contains a world in which sharp angles and surreal imagery juxtapose beautifully with idyllic descriptions of nature, never setting one apart from the other. Every sentence combines the sights of water and gardens with the strange confines that birth them, cycling between a fundamentally human description of the world and an inescapably acculturated nature that glows in its tense, generous images of wind and leaves and shrubberies.”

Gardens by Carlos Cociña reviewed by Diego Alegría in Latin American Literature Today:

"...masterfully translated by Ian Lockaby, the Chilean author avails himself of the fragmented connection of nine works of poetic prose, anchored at the syntactic level through parataxis to connect physical and psychological gardens, expansive and minuscule, visual and tonal."

Listed in “Favorite Books of Poetry in Translation 2021” by Action Books

The Dream of Every Cell ︎︎︎

“Dreams of Cells and Wolves.” Constance Hansen on The Dream of Every Cell in Poetry Northwest:

“The book calls for dissent, mourning “the biodiversity that suffers the kinds of transfers calculated in agroeconomic offices where no dissenting voices sound.” Yet, a generous spirit enumerates what forms such dissent might take; like the wolves they so often reference, these poems are playful yet fierce.”

“The Dream of Every Cell is a manifesto of caretaking, caregiving, and all that is lifegiving; it reaches for a common language that can restore the world to wholeness.”

The Dream of Every Cell by Maricela Guerrero reviewed by Alec Schumacher in Make Lit:

“The poems themselves seem to grow from previous ones, building a particular lexicon that becomes enriched with each poem. Aloe vera, wolves, birch and fir, anemone, subtraction, breath, nitrogen, empire: these words become more tangible as each poem gives shape to their meaning in Guerrero’s diction. The book reveals itself as organism, as a structure of interrelated cells that communicate and feed each other. And just as biological information is imprinted during the process of reproduction, the book is a space that receives poetic information.”

“Every translation effectively constitutes an interpretation, yet Myers translation flows openly like a parallel river to Guerrero’s Spanish, nimbly bending between registers following Guerrero’s odyssey through cells, roots, chemical processes, and human relationships.”

The Dream of Every Cell by Maricela Guerrero reviewed by Bret Ameneyro in Los Angeles Review:

“If viewed as a collection of essays, the thesis can be found on the last line of the poem “Cells”: “I’d like to know if there will be room for all of us.” The speaker often jumps from nature imagery to images of buildings and human-made structures to show the constant battle for space on our planet. “The empire” is portrayed as an invasive species that fights against plants and animals.”

The Dream of Every Cell by Maricela Guerrero reviewed by Greg Bem in North of Oxford:

“The Dream of Every Cell is a cunning array of poetic explorations, and it is a book of dreams. It is a book of longing and the imagination.”

“Guerrero’s collection, (...) feels as much a collection of poetry as it does a document of rebellion, a manifesto, a toolkit on how to think about connectedness and ecology.It is a book about individuals as much as it is about systems. It is a book about personal commitment as much as it is a book about relationships.”

Contra Natura ︎︎︎

Contra Natura by Rodolfo Hinostroza reviewed by Olivia Lott in Action Books:

“Thanks to translator Anthony Seidman and publisher Cardboard House Press, Hinostroza’s 1971 masterpiece has made its long-anticipated debut in English. Octavio Paz praised its potential to shake Latin American poetry early on, and some compare its risk-taking impact to that of fellow Peruvian César Vallejo’s iconic Trilce (1922). The collection is known for its incorporation of symbols (zodiac signs, mathematic equations, a compass), its multilingualism (English, French, Italian, and Latin, alongside the Spanish), and dense referentiality (Hamlet, the bubonic plague, the Cunningham chess defense, Archibal MacLeish, Anteaus, just in the first poem). This is certainly a difficult text to translate, and Seidman rises to the task. His version crisply shapeshifts to match the fluctuating demands and demanding fluctuations that Hinostroza places on the lyric.”

Contra Natura by Rodolfo Hinostroza reviewed by César Ferreira in Latin American Literature Today:

"The publication of this bilingual edition of Contra Natura (1971)...deserves the highest praise, as it brings the work of one of the most important Peruvian poets of the second half of the twentieth century to an English-speaking audience.”

“Contra Natura is a disturbing book that is full of surprises. The work is a product of a unique grammar and a complex system of signs that creates its own semantic field.”

Contra Natura by Rodolfo Hinostroza reviewed by Greg Bem in North of Oxford:

“At long last, the Peruvian poet Rodolfo Hinostroza’s majestic Contra natura is available to the English-speaking audience. This work is a crucial component of late 20th-century poetry attuned to the modernist collecting, the surrealist melting, and the complex humor that follows the community footsteps of poets throughout South America.”

Contra Natura by Rodolfo Hinostroza reviewed by Irakly Qolbaia in Caesura Magazine:

Though there may currently be no room for literary revelry, I think there is one book a centennial of which we should be, if not celebrating, at least actively contemplating―more than Ulysses, more than Duino Elegies or My Sister, Life, even more than The Waste Land―albeit surely where we are, full circle and back at―is César Vallejo’s Trilce, which hit the world the same year as the abovementioned celestial bodies, and, although less heeded, it might yet prove to be the Poem of that century, and the poem for our own arrested day. But maybe all the works I dropped the titles of, seemingly related by the year of their publication (and the poem we are celebrating in this text, and will get to in a bit, is the poem written by a poet-astrologer, so there can be nothing merely seeming about the dates in our current contemplation) are the works of the counter-nature, Contra Natura, in their contradistinct and unique ways, shedding light on the condition of the human Soul’s alienness to this Earth (Es ist die Seele ein Fremdes auf Erden, in the words of Georg Trakl, words that seem to epitomize the modern man’s twisted vision of soul’s counter-nature condition).

Boat People ︎︎︎

Boat People by Mayra Santos-Febres reviewed by Meaghan Coogan in Asymptote:

“Boat People endeavors to document the undocumented, the invisibilized, and the silenced who are lost to the sea.”

“Santos-Febres’s Boat People documents the Black lives lost in the attempt to chase the mirage of the American Dream, in order to combat the silence and absence of archival records and humanizing discourse surrounding Black death, which is often reduced to numbers in a newspaper article or spectacularized violence in a photograph.”

Boat People by Mayra Santos-Febres reviewed by Katherine Hedeen in Modern Poetry in Translation:

“Thanks to translator Vanessa Pérez-Rosario and the tireless work of independent publisher of poetry in translation Cardboard House Press, U.S. readers are asked to question how borders are defined; to go beyond the anti-immigrant rhetoric of wall-building; to look east rather than south; to think of the sea.”

Boat People by Mayra Santos-Febres reviewed by Shash Trevett in The Times Literary Supplement:

“Brilliantly translated into English for the first time by Vanessa Pérez-Rosario, the book-length poem possesses a lyrical intensity enfolding centuries of desperate water crossings. It is a migration elegy and an oceanic hymn that mimics the creative and destructive power of the sea.”

Boat People by Mayra Santos-Febres reviewed by Greg Bem in

Exacting Clam:

“The fatalism is amplified by a swollen language of stories of unacknowledgment and brutal survival: “identity unquestioned / and one more to the sea / a watery wilderness” (35). The poet calls forth the fragmentation of our discourse, at large, around the subject of migration along the margins, of consideration of refugees.”

Boat People by Mayra Santos-Febres reviewed by Zack Anderson in

Harvard Review:

Boat People by Mayra Santos-Febres reviewed by Honora Spicer in

World Literature Today:

“Gnashing and disassembling flesh and language at once, “la fauce azul / alafau sea sul,” Pérez-Rosario’s translation sustains this simultaneity and breakdown: “like the yawl that tossed your excess weight / into the blue maw / intothe bluem aw.” This spacing, repetition, reordering of proximity gestures toward bodies opening out in multiple ways, becoming un-numberable, un-indexical, un-categorizable.”

“The Opacity of Language, the Empathy of Translation,”

Aitor Bouso Gavín on Boat People in Hopscotch:

Boat People by Mayra Santos Febres reviewed by

Zoe Contros Kearl in Kenyon Review:

“Mayra Santos-Febres’s collection Boat People, translated by Vanessa Pérez-Rosario, addresses the oft-undiscussed topic of undocumented migration in the Caribbean. In a numbered series of poems that are sparse and beautiful and rending, both in form and in content, Santos-Febres creates devastating narratives time and again.”

Listed in “Favorite Books of Poetry in Translation 2021” by Action Books

Carnation and Tenebrae Candle ︎︎︎

“Burning Like Roses: On Marosa Di Giorgio’s Carnation and Tenebrae Candle” by Zack Anderson in Action Books:

“Clavel y Tenebrario / Carnation and Tenebrae Candle by Marosa Di Giorgio, Translated by Jeannine Marie Pitas” by

Juan de Marsilio in

Latin American Literature Today:

Carnation and Tenebrae Candle by Marosa Di Giorgio reviewed by

Honora Spicer in Asymptote:

“The pastoral genre is always political insofar as it concerns the scope of the city as well as the ways that people tend to the edges of the polis. This act of tending is performed again and again in Carnation and Tenebrae Candle, and these habits of interaction between humans and the natural become ways of world-making, which is a prominent impulse of di Giorgio’s. In this collection, translation is another tending—the world-making of repeated care—and Pitas’s translation is best described by a line from the collection: “everything there, meticulous, tender and nearly trembling.”

Carnation and Tenebrae Candle by Marosa Di Giorgio reviewed by Greg Bem in North of Oxford:

Carnation and Tenebrae Candle by Marosa Di Giorgio reviewed by

Rose Bialer in Kenyon Review:

“Through her engagement with di Giorgio’s poetry, Pitas invites a new audience to witness the power of imagination and the possibilities that it offers: the capacity for curiosity both in the quotidian moments and the horrific. Originally published in 1979 during the time of Uruguay’s military dictatorship, Carnation and Tenebrae Candle is a timely translation for contemporary English-speaking readers. In our own tumultuous times, di Giorgio’s words are an immense comfort, showing us the potential for humanity and creation in the face of brutality and destruction.”

Pixel Flesh ︎︎︎

Pixel Flesh by Agustín Fernández reviewed by

Vincent Moreno in

Angel City Review:

“Pixel Flesh is a highly intertextual work that opens up all sorts of hallways and windows into other forms of art, into other texts and disciplines. The references are sometimes direct: Blade Runner, Wittgenstein, Warhol, and pop music, among others, appear in the book as a very eclectic and, in appearance, incongruous amalgam of quotes and allusions that are a trademark of Fernández Mallo’s style. Ultimately, however, it is the reader who holds the key to venture into new doors and corridors. This makes each new reading of the book a new experience, rendering it practically inexhaustible in connotations and suggestiveness.”

Pixel Flesh by Agustín Fernández Mallo reviewed by Greg Bem in Rain Taxi:

“Behind the eyelids or in front of them, the world is awash with information; this information contains patterns and poems, and pushes the field further. Pixel Flesh is fascinating as a paper book that relays concepts more often suited for screens. Calling into question so many aspects of our postmodern reality, Mallo has written a book for the present. It may not read comfortably, but it is, like the black holes regularly mentioned, both vast and dense at once.”

Pixel Flesh by Agustín Fernández Mallo reviewed by

Honora Spicer in

World Literature Today:

“The translation becomes itself a rich commentary on the representation of fractal self-similarity. Ludington explores how to knowingly translate oddness in the original, exposing the valences of fractal deriving from the Latin for ‘broken’ or ‘fractured.’”

“Mallo’s interest in writing through cultural detritus informs this approach of using a set of trite tropes that generate a loop and ultimately demonstrate the deterioration of meaningful human connection in the face of technological static.”

Pixel Flesh by Agustín Fernández Mallo reviewed by

AM Ringwalt in Kenyon Review:

“Ludington’s translation, through its verbal re-presentation of Mallo’s circling poetics, effectively intensifies Mallo’s project, demonstrating a generative absence beyond memory and beyond language. Everything is unsettled; from this site of unsettledness, where even language is without center, Ludington translates around the impossibility of grasping absence.”

(ESSAY) “Love as a Question of Destination in Agustín Fernández Mallo’s Pixel Flesh” by

Eleanor

Tennyson in

SPAM:

Garrett Phelps on

Agustín Fernández Mallo’s

Pixel Flesh in Asymptote:

“He’s an Impressionist, in other words, albeit a hypermodern variant whose range includes the landscapes of cyberspace and information overload. As subjects these are slippery and mercurial, but Mallo adapts to unplanned contingencies like a plein air painter would to weather.”

Room in Rome ︎︎︎

Letters From Latin America: Room in Rome by Jorge Eduardo Eielson reviewed by Leo Boix in Morning Star:

“Eielson weaves personal history with geographic location, homosexual desire with longing, past and future, in a fashion that is as playful as it is profound.”

“Nota Benes, Autumn 2019,” World Literature Today:

“Room in Rome captures Eielson’s remarkable sensitivities to the places and cultures in which he immersed himself, and this new translation reintroduces one of Latin America’s most important wordsmiths to the English-speaking world.”

Room in Rome by Jorge Eduardo Eielson reviewed by César Ferreira in Latin American Literature Today:

“Room in Rome (1954), now appearing in a bilingual edition with David Shook’s magnificent translation in English, a prologue by Mario Vargas Llosa and an epilogue by Martha Canfield, is both a showcase of Eielson’s poetic excellence, and an individual and collective reflection on his exile in Europe.”

“Slipknots: Jorge Eduardo Eielson’s ‘Room in Rome,’ Translated from Spanish by David Shook” by

Olivia Lott in

Reading in Translation:

“The question most pertinent for Eielson’s and Shook’s poems, however, is what vanishes for the exile? What knots fall apart when tensed? What attempts to tie something together, to re-articulate slip away, drop out of reach?”

“The Singing Knots of Jorge Eduardo Eielson: Room in Rome in Review” by

Sergio Sarano in Asymptote.

Cartonera Collective Series ︎︎︎

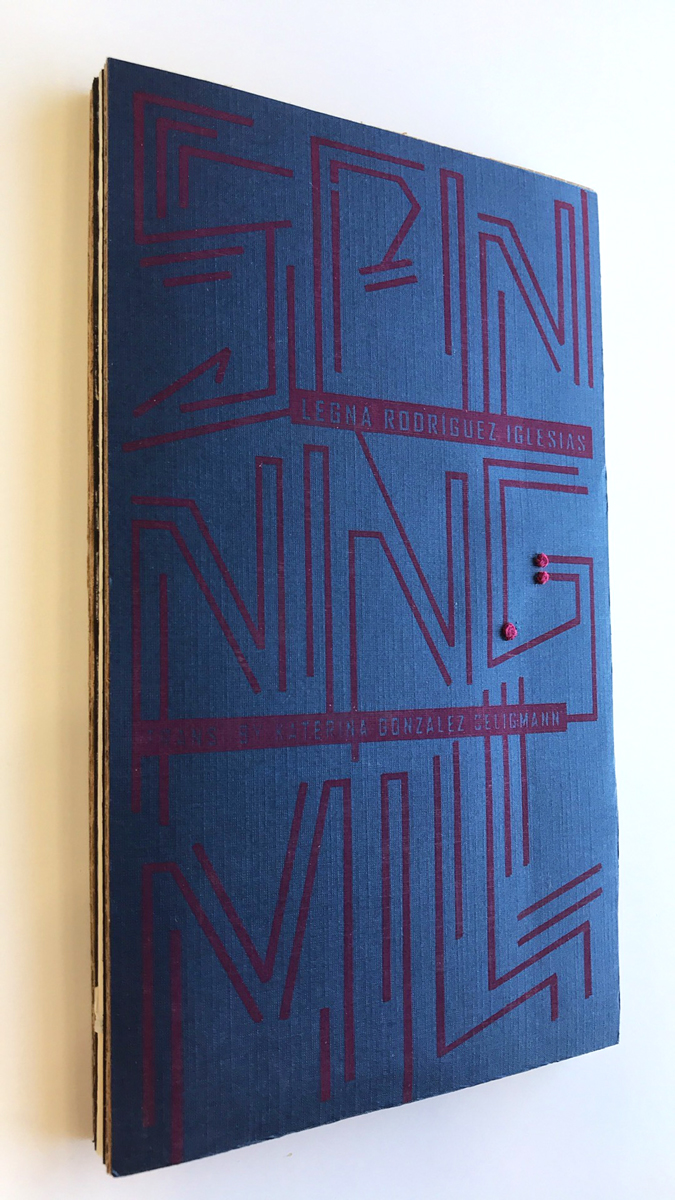

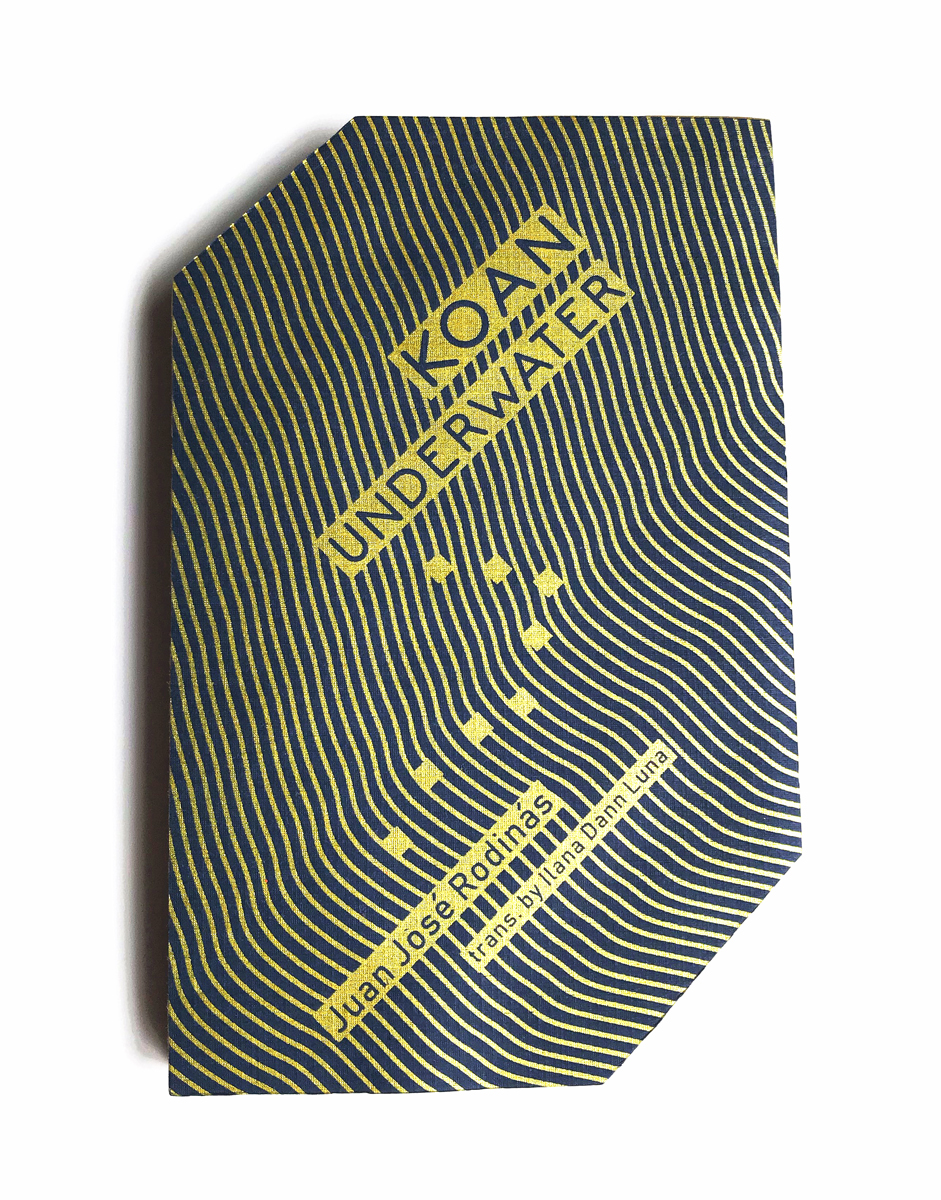

Cartonera Collective Series (Maricela Guerrero’s Kilimanjaro, Juan José Rodinás’s Koan Underwater, Legna Rodríguez Iglesias’s Spinning Mill) reviewed by Clara Atfeld in Kenyon Review:

"All of these books focus on redefinition in some form, making them enchanting translated work, as that redefinition has had to take shape in two different languages. The books themselves are beautiful, handmade pieces, that fit the project of the poetry. Kilimanjaro folds out into an accordion, creating the largest track illustrated in the book. Spinning Mill and Koan Underwater shift the orientation of the words on the page, shifting the orientation of the reader to the words, to poetry, to translation, all at once. The Cartonera Collective’s project makes not just the literature but the publication process itself a multicultural translation."

“Legna Rodriguez Iglesias focuses on redirecting logic, taking the reader through a logical sequence with seemingly illogical steps...The poetry focuses on gender, love, and race, through the lenses of absurdity and honesty.”

“Cardboard Conscious: Translation in Community” by

Kelsi Vanada in

Reading in Translation:

![]()

“The poems honor process—the process of textile work, the process of women defining themselves and seeking equality in a society dominated by the patriarchy (...) And the book shows off its process, too: in the waxed thread that holds the pages together, the decorative knots embroidered in deep pink thread on the cover, and in Seligmann’s translation process and choices placed right next to the original.”

![]()

“Kilmanjaro is nothing if not a long list-rant against capitalism and the forces that make people cogs in a machine—and if that sounds negative, good. It’s supposed to be uncomfortable”

“A Report from the Cartonera Collective” by

Fields, Noa/h in

ANMLY:

![]()

“I allowed the surreal, associative drift of Rodinás’s poems to wash over me like a dream (...) Rodinás’s koans resurface from underwater logic, ripple with doublings and eery (eary?) recurrences in musical sequence. A hearty recommendation for Koan Underwater: yet another hit from Cardboard House Press.”

Lyric Poetry is Dead

︎︎︎

“An Interview with Robin Myers, Translator of Lyric Poetry Is Dead by Ezequiel Zaidenwerg” by Heather Lang in The Literary Review.

“~Notes on a Journey to the Ever-Dying Lands~” Lyric Poetry Is Dead by Ezequiel Zaidenwerg reviewed by Arturo Desimone in ANMLY:

“Fortunately, Lyric Poetry is Dead quickly reveals itself as a protest—only half-cynical, elsewhere tender—against the hegemonic and academic forces of antipoetry, making it in places a genuinely antagonistic collection.”

Lyric Poetry Is Dead by Ezequiel Zaidenwerg reviewed by Madeline Vardell in The Arkansas International:

“Lyric poetry becomes both the vehicle for Zaidenwerg to reimagine many histories and allude to other literary greats, and the poetic subject and star of her own legends. Just so, Lyric Poetry Is Dead is waiting to rise up like Lazarus and delight you over and over again.”

Lyric Poetry Is Dead by Ezequiel Zaidenwerg reviewed by Paul Guillén in Latin American Literature Today:

“Zaidenwerg uses tropes of traditional poetry and breaks them like someone who is rummaging, like an investigative poet.”

“Lyric Poetry Is Dead: The Flourishing Obituary of Ezequiel Zaidenwerg” by

Bill Mohr in Koan Kinship.

Testimony of Circumstances

︎︎︎

“Rebel Poetry: Rodrigo Lira’s Testimony of Circumstances in Review” by

Garett Phelps in

Asymptote:

“Needless to say, all of Lira’s neologisms, wordplay, intertextuality, and assonance-based rhythms would cost even the best translator a pint of blood. Ours, however, are the best of the best and have pulled off an English that’s as shining, breathless, and combustible as its source. It’s often just as inventive, too.”

Testimony of Circumstances by Rodrigo Lira reviewed in The Arkansas International:

“Lira may have written in the 70s, in response to the oppressive climate of his own government, but hold his poetry up and it is an unnerving lens for the present day, America and elsewhere. We should all take up the pen, like Lira, write against the suffocation of the factory, but first, turn to Testimony of Circumstances, enter into conversations with Lira and beat back our solitary sub-lives, choose to hear, more than survive.”

Testimony of Circumstances by Rodrigo Lira reviewed by

John Venegas in Angel City Review:

“What Testimony of Circumstances represents then is a kind of pseudo-biography, a fascinating, disarming, and brilliant cross section of a life dedicated to literature. Everything is on display here – Lira’s politics, his contentious rivalries with those he wanted to regard as friends and/or peers, his utterly merciless inner voice – all of it. There is a richness of perspective present that caught me rather off guard.”

Testimony of Circumstances by Rodrigo Lira reviewed by

Jasmine V. Bailey in Waxwing Literary Journal: American Writers & International Voices.

Album of Fences

︎︎︎

Album of Fences by Omar Pimienta reviewed by Kelsi Vanada in Kenyon Review:

“That’s the strength of this hybrid photo-poem collection—it humanizes a complex place that is a hot-button issue for many. For Pimienta, it’s home.”

“Nota Benes, Autumn 2018,” World Literature Today Album of Fences:

“This collection is a fascinating combination of poetry (presented in both Spanish and English en face) and photography portraying the duality of living on the US/Mexican border through personal anecdotes and photos. With little punctuation or capitalization, the pieces feel dusty yet hurried, as if rushing to convey meaning against a backdrop of transnational urgency.”

Garrett Phelps on Agustín Fernández Mallo’s Pixel Flesh in Asymptote:

“He’s an Impressionist, in other words, albeit a hypermodern variant whose range includes the landscapes of cyberspace and information overload. As subjects these are slippery and mercurial, but Mallo adapts to unplanned contingencies like a plein air painter would to weather.”

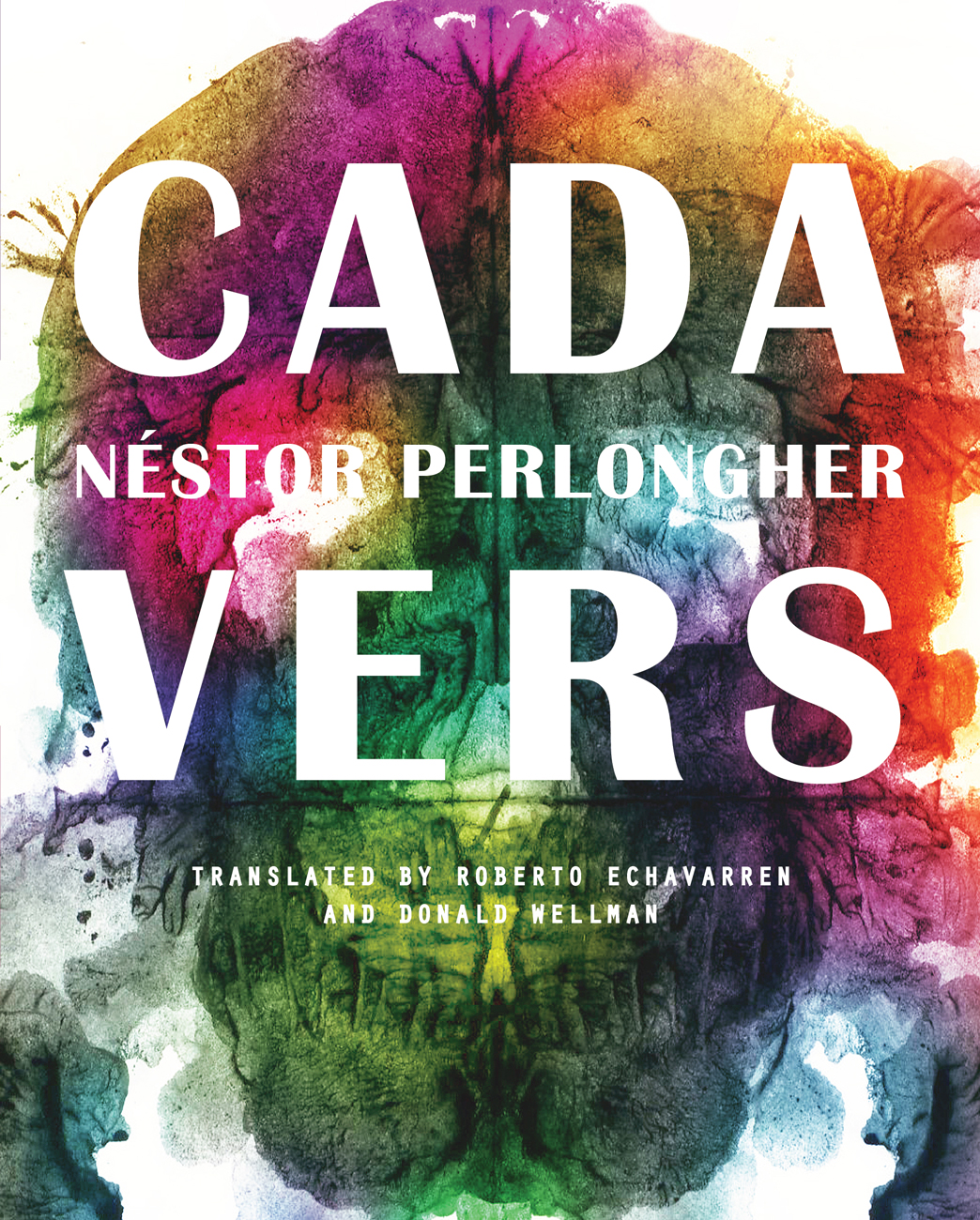

CADAVERS

Néstor Perlongher